Ten remarkable new marine species from 2020

Release date: March 19th 2021

- The E.T. Sponge, Advhena magnifica

- The Patrick Sea Star, Astrolirus patricki

- The Branch-Armed Nostril Copepod, Dendrapta nasicola

- The Yellow Sea Slug of Ørland, Dendronotus yrjargul

- The Giant Plastic Amphipod, Eurythenes plasticus

- Haffi’s Upside-Down Tapeworm, Gyrocotyle haffii

- The Beautiful Branching Bryozoan, Hornera mediterranea

- The Tree-of-Life Tardigrade, Neoechiniscoides aski

- The Feisty Elvis Worm, Peinaleopolynoe orphanae

- Red Wide-Bodied Pipefish, Stigmatopora harastii

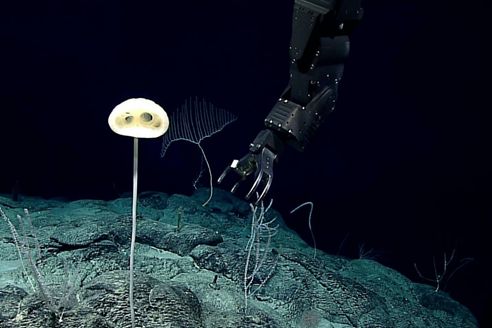

The E.T. Sponge

Advhena magnifica Castello-Branco, Collins & Hajdu, 2020

The E.T. Sponge, Advhena magnifica was spotted by a team of NOAA explorers that were searching the sea floor of the Pacific Ocean. Over 2 kilometres below the surface, the explorers were amazed to come across a deep-sea environment studded with strange and beautiful animals that looked more like an alien landscape than something found on Earth. This area was dubbed the “Forest of the Weird” in reference to many forms of gorgeous, delicate, glass sponges seen growing along the sea floor like an alien forest.

Among these strange glass sponges was the new species Advhena magnifica (Latin for “magnificent alien”). Growing high on its stalk like an elongate mushroom, the sponge is adorned with large openings that face into the current so it can filter small food items from the water. The round body of the sponge with its two openings looking like eye sockets was reminiscent of the head of the alien from the beloved movie E.T. – the Extra Terrestrial, and earned this sponge its common name, the E.T. Sponge.

While this sponge and many others in the “Forest of the Weird” may look like mushrooms or otherworldly plants, they are, in fact, animals with specially shaped bodies filled with intricate canals through which they pump water to collect food (minute particles like bacteria) from the passing current. Advhena, as other glass sponges, uses a syncitium (multinucleate cell) to collect its food.

In fact, these glass sponges get their name from the silica skeleton they build to support themselves and deter predators. The skeleton is made from spiny silica structures called spicules that take various forms but often look like some combination of caltrops, jacks, or Czech hedgehogs. In fact, it was the unique spicules of Advhena magnifica that alerted scientists that it was not just a new species, but also a new genus of glass sponge.

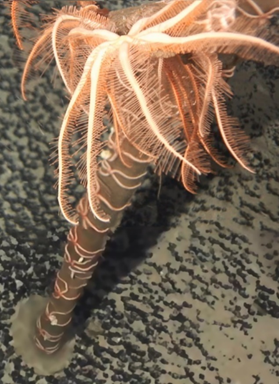

The Patrick Sea Star

Astrolirus patricki Zhang, Zhou, Xiao & Wang, 2020

This new species of starfish is named after Patrick Star from the beloved cartoon SpongeBob Squarepants. It was discovered in the depths of the northwestern Pacific Ocean at a few locations 1.5-3 km below the surface. It gained its name not from the pink-red colour it shares with Patrick Star, but more aptly from its close association with another species – a sponge! All five specimens of the new starfish species were found attached to deep-sea sponges.

In the paper describing this new species, the authors write that the name originated from the character ‘Patrick Star’, who always spends time with his best friend SpongeBob, a benthic sponge. Since all specimens of the new species were observed living on sponges, it was named after Patrick to reflect this curious relationship.

However, unlike the cartoon character, this new starfish species boasts seven arms, which are much more slender than the rotund, five-armed Patrick Star we are familiar with. In fact, the new species can be distinguished from other related sea stars based on the number of arms and spines it has, as well as other smaller structures call costae and intercostal plates. As for other deep-sea friends, Squidward Tentacles may still be out there waiting to be discovered.

The Branch-Armed Nostril Copepod

Dendrapta nasicola Irigoitia, Taglioretti & Timi, 2020

Copepods are small crustaceans that are found in all aquatic habitats, both marine and freshwater. Many copepods are herbivores or predators, but there are also thousands of species of parasitic copepods, like the new species here. Among its parasitic brethren, the Branch-Armed Nostril Copepod, Dendrapta nasicola, is unique in all the ways its name suggests: it has branched, root-like arms (more accurately called maxillae) and it lives in the nostrils of its host, the skate Bathyraja scaphiops. Its highly branched “arms” are modified appendages that this species uses to attach to the inside of the nostril of the skate. Disturbingly, the branched arms grow into the tissue of its host, permanently securing the parasite inside the nostril and making their removal very difficult. Much to the infected host’s chagrin, skates don’t even have a finger to pick their nostrils with!

This species was discovered following the careful examination of skates caught in waters off of Buenos Aires province, Argentina. The copepod appears to be host specific, because it was found on only one species of skate, although the scientists describing it examined over 20 other kinds of skates. This skate species is potentially vulnerable to a population decline due to current fishing pressure, which is very intense in the endemic zone. This means that the new copepod, which relies on this host, is also potentially threatened.

The only other species of Branch-Armed Copepod (Dendrapta cameroni) was known from the skin of a number of different skate species in the Northern Hemisphere. The new species is different from the other species of Dendrapta because it is larger, longer yet more narrow, and has some other differences in its appendages including hair-like structures called setae. The finding of this species not only in the Southern Hemisphere but also in the nostril of a skate was surprising. The species name “nasicola” refers to its habitat – the nostril of its host.

The Yellow Sea Slug of Ørland

Dendronotus yrjargul Korshunova, Bakken, Grøtan, K. B. Johnson, Lundin & Martynov, 2020

What do Facebook, SCUBA divers, and scientists all have in common? They were all instrumental in discovering and describing the Yellow Sea Slug of Ørland! This sea slug was first noticed and photographed in 2014 by SCUBA diver Kjetil Johnson in Trondheimsfjorden, one of the largest Fjords in Norway. Three years later, another diver, Viktor Grøtan, photographed the animal again. Both divers took to social media and posted their photographs in the Facebook group “NE Atlantic Nudibranchs”. After seeing the images from the Facebook group, scientists secured collection permits and asked the divers to collect some of the sea slugs they had photographed. The divers agreed and provided specimens to a team of scientists, and they all worked closely together to describe the new species! Both SCUBA divers were recognized for their contribution and co-authored the publication with the team of scientists. The new species is named Dendronotus yrjargul in reference to the locality, ‘Yrjar’ which was the old name for Ørland, and ‘gul’ referring to its yellow or golden markings.

In their paper on the Yellow Sea Slug of Ørland, the team not only described the new species, they also revised the entire genus Dendronotus, a group of 27 closely-related species. The publication includes beautiful photographs of live animals, high resolution microscope images, and DNA sequencing in order to document difference between the species. The authors showed that the new species was unique in a number of ways, most notably the yellow frosted tips on the branching gills on its back. The description of this species is an excellent testament to how scientists, outdoor enthusiasts, and social media communities can work together to discover new things!

The Giant Plastic Amphipod

Eurythenes plasticus Weston in Weston, Carrillo-barragan, Linley, Reid & Jamieson, 2020

Describing a new species provides a unique opportunity to capture the minds and hearts of the public and inspire them to become better environmental stewards. One of the many anthropogenic threats facing our ocean is plastic pollution. This year, a new scavenging amphipod crustacean was discovered living 6 to 7 km below sea level in the Mariana Trench, the deepest place on earth. It is the ninth species of Eurythenes to be described, possessing a unique suite of morphological features and is part of a distinct genetic lineage. While every new species is an achievement for science, in this case, one of the 11 specimens was found to have microplastic in its digestive tract. That microplastic fibre was 84% similar to PET, the main polymer in plastic bottles. This represents a tragic milestone; the first-time plastic has been documented in a new species. The new species was given the name ‘plasticus’ to symbolise the ubiquity of marine plastic pollution.

This scavenging amphipod from the Mariana Trench in the Pacific Ocean is small in size but has made a mighty impact. The species has come to symbolise our environmental impact on parts of the world that we are yet to even discover. Within hours of publication in Zootaxa, a worldwide conversation through news outlets and social media ignited over the extent of plastic pollution in our oceans. The story of Eurythenes plasticus continues to make a lasting impact through films, several permanent museum exhibits, and a dedicated educational website (https://www.plasticus.school/en/).

Eurythenes plasticus tells a story of deep-ocean exploration and modern-day scientific discovery of a new species, and, most importantly, highlights how our daily actions can impact animals, even in the deepest and most remote parts of the ocean.

Haffi’s Upside-Down Tapeworm

Gyrocotyle haffii Bray, Waeschenbach, Littlewood, Halvorsen & Olson, 2020

Tapeworms are strange yet amazing creatures that have fascinated people for hundreds of years. Just imagine how weird life would be if you had no digestive tract, no stomach or intestine, not even a mouth – yet this is exactly how a tapeworm lives quite happily. Instead of eating their own food, a tapeworm lives in the intestine of another animal and uses its specialized skin to absorb the already digested nutrients from its host.

Even among tapeworms this new species is an oddball. It belongs to the order Gyrocotylidea, a group of just 17 species that are the distant cousins of all other tapeworms. Like a relic from ancient times, these worms are very different from other tapeworms. While all other tapeworms have a specialized attachment structure at their head-end called a scolex, gyrocotylideans have only a simple suction cup structure at that end, but they sport a complex, flower shaped adhesive organ, called a rosette, at their tail. This rosette superficially resembles a scolex, hence the name used here: upside-down tapeworm.

Gyrocotylidean worms are also short and stout with frilly margins, not long and flat-bodied like the tapeworms people may be more familiar with. Most tapeworms are long and segmented, but their flatworm ancestors were not, and these evolutionary cousins to the tapeworm may be more similar to the form of the 'proto-tapeworm' than to the segmented tapeworms we are more familiar with today.

The ancient ancestry of gyrocotylidean tapeworms is mirrored in the hosts they parasitize. Gyrocotylideans live only in the intestines of holocephalans, a group of cartilaginous fish also known as ratfish, chimeras, and ghost sharks, which themselves are distant cousins of sharks and rays. These tapeworms and their hosts have likely existed together for 400 million years! While there is a rich fossil record of many holocephalans dating back to the Devonian, there are only 39 species living now. It may be that there were once many more gyrocotylideans living in these now extinct animals, but now only a small number of surviving species remain in the oceans today.

This new species is named in honour of Professor Harford ‘Haffi’ Williams in recognition of his contribution to the understanding of this group of tapeworms.

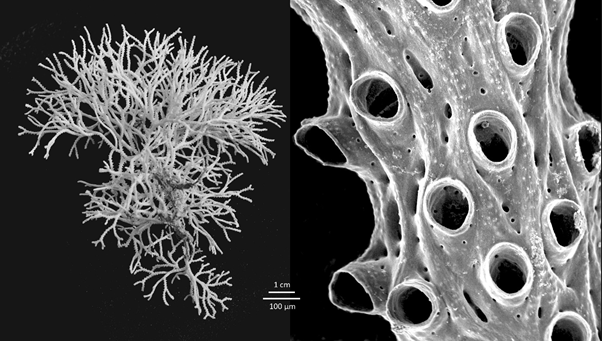

The Beautiful Branching Bryozoan

Hornera mediterranea Harmelin, 2020

Bryozoans are a largely overlooked group of colonial invertebrates that live in aquatic environments worldwide. The colonies of different species are found in a variety of forms, from encrusting types that grow on a substrate such as rock, shells or seaweeds, to those that build exoskeletons resembling corals. This new species is one of the beautiful branching bryozoans and is found in the Mediterranean Sea, perhaps one of the best studied seas in the world. This new species has been overlooked because of problems in the naming of the known species for more than a century.

The description of this new species of bryozoan, Hornera mediterranea, was achieved following lengthy investigations of a “cold case” involving unresolved questions incorporating both taxonomic and conservation issues.

It was necessary to first find out which species was hidden behind the name Hornera lichenoides (Linnaeus, 1758), which is a species known from Arctic and northerly waters, and was designated as the only bryozoan to be strictly protected in the Mediterranean Sea, which is where the confusion began. Perhaps this name actually referred to the well-known Hornera frondiculata (Lamarck, 1816), or perhaps to another species? Hornera frondiculata, thanks to its large size and the beauty of its branching design, was one of the first bryozoans to be pictured by ancient naturalists. It was also necessary to find out the identity of the unnamed, slender and delicately branching Hornera species which coexisted in the Mediterranean Sea along with H. frondiculata.

Characterization of cyclostome bryozoan species is not an easy task, but thanks to the comprehensive study of abundant material, from depths of 55–220 m, collected by diving and dredging around Marseille over the last 50 years, and the use of scanning electronic microscopy, we now have a clear understanding of this new species.

The name given to the species, Hornera mediterranea, is a tribute to A.W. Waters, an English naturalist who had recognized the existence of a second Hornera species in the Mediterranean. He had proposed the species name mediterranea in 1904, but because it was not described and there was no type specimen, this was not recognised… until now.

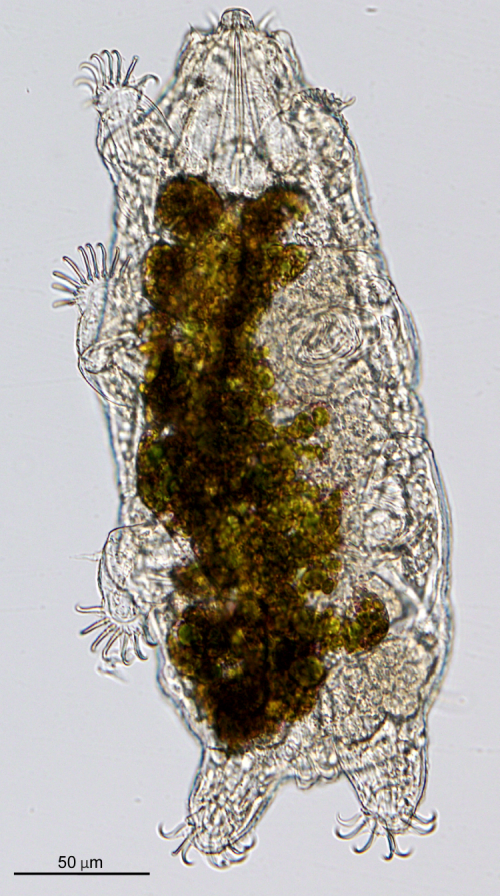

The Tree-of-Life Tardigrade

Neoechiniscoides aski Møbjerg, Jørgensen & Kristensen, 2020

Tardigrades, also known as water bears, are a fascinating group of microscopic animals with four pairs of short legs that are famous for their ability to survive extreme conditions of temperature, pressure, starvation and dehydration. The best-known tardigrades are found in terrestrial environments among mosses, but they are found everywhere in the world, from the tops of mountains to the depths of the ocean, and there are many species that live in the marine environment.

This new tardigrade was discovered living in sandy sediments in the intertidal zone of a bay in Roscoff in France that falls dry at low tide. The animal is indeed tiny, at around one third of a millimetre, but for a marine tardigrade it is considered of medium to large size! It is distinguished by having three annulated mouth rings (instead of two mouth plates) that it uses to telescope the mouth cone. These tardigrades are also recognised by their unique anal system which has a set of wing-like structures associated with the side lobes.

The finding of this new genus and species of tardigrade further highlights the exceptional diversity of these enigmatic creatures in tidal zones.

As a tribute to these interesting findings, which have implications for the relationships of these animals in the evolutionary tree, it is named N. aski, for Ask Møbjerg Jørgensen, the child of two of the study’s authors, who is in turn named for the Nordic mythological 'tree of life', Ask Yggdrasil.

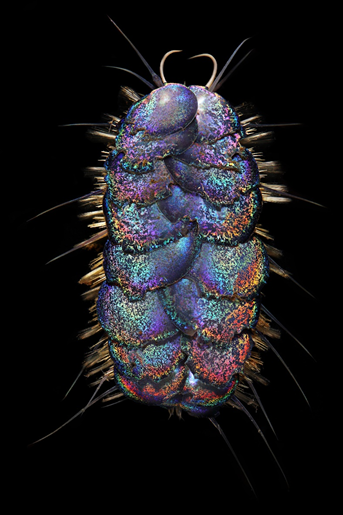

The Feisty Elvis Worm

Peinaleopolynoe orphanae Hatch & Rouse, in Hatch, Liew, Hourdez & Rouse, 2020

Peinaleopolynoe is a group of remarkable scaleworms native to deep-sea chemosynthetic-based ecosystems, including methane seeps, hydrothermal vents, and organic falls (e.g. whalefalls). These scaleworms have evolved to tolerate low oxygen levels by having elaborate gills under their scales. The authors had for many years nicknamed these sparkly scaleworms ‘Elvis worms’ because their scales resembled the sequins on Elvis’ signature attire. This nickname is honoured by the naming of one of their new species as Peinaleopolynoe elvisi.

We chose another species, Peinaleopolynoe orphanae for the Top-Ten Marine Species for 2020, as it is perhaps the most exciting of the four new species described in Hatch et al. (2020), having both the most stunning iridescence and the feistiest temperament! Known from enriched deep-sea environments from 2900–3700 m, on microbial mats at hydrothermal vents in the Pescadero Basin (Mexico) and on a clam bed near a seep in the Monterey Canyon (California), Peinaleopolynoe orphanae serves as an emblem for deep-sea biodiversity.

The sparkling iridescence appears to be due to a thickened cuticle of the scales, which may be protective, rather than for communication purposes. The namesake of the species (Dr Victoria J. Orphan) managed to capture remarkable footage, from the ROV camera, of the worms fighting (and ‘jitterbugging’!) in their natural habitat. The two individuals can be seen interacting and attacking one another back and forth for several minutes. This may explain the damaged scales with apparent bite marks on the edges, which can be seen in the specimens collected (see video).

Red Wide-Bodied Pipefish

Stigmatopora harastii Short & Trevor-Jones, 2020

This colourful new species of pipefish has been chosen for the Top-Ten for its clever camouflage, among red algae and sponges, and the fact that it has been described from Sydney’s underwater doorstep, a popular dive site where it has been hiding for years without anyone realising.

It was soon realised that this represented a new species of Stigmatopora based on the unique colour, habitat and depth in which it was found. Like all members of Stigmatopora, the new species has a long snout and thread-like prehensile tail, but it has a bright red body, unlike the green or brown of other species in the genus.

The Red Wide-Bodied Pipefish, Stigmatopora harastii is known from central New South Wales, Australia from just three localities, in Botany Bay, Shellharbour, and Jervis Bay, where it occurs in semi-exposed bay entrances and ocean embayments in sandy areas, interspersed amongst rocky reefs at depths between 12–25 metres.

These habitats are subject to strong surges where the fish are often observed swaying in unison with red algae or associated with pale red finger sponges. Their red colour and body orientation make them extremely well-camouflaged among the red algal fronds. So well-camouflaged in fact, that it took co-author Andrew Trevor-Jones three months of searching his regular dive sites in Botany Bay to determine if the red pipefish also occurred there. With the aid of a dive torch at 12 m deep, he was eventually able to confirm the presence of the species swaying with the algae.

The species is named after David Harasti, one of the first to recognize S. harastii as being a new species, in recognition of his efforts towards conservation. According to the authors, David has stated that he counts pipefish to fall asleep!

This recent discovery of such a charismatic fish highlights how much we still have to learn about the diversity of fishes in southern Australia, and how easy it is to overlook such well-camouflaged animals.

Sources

The E.T. Sponge

Original source

Castello-Branco, C.; Collins, A.G.; Hajdu, E. (2020). A collection of hexactinellids (Porifera) from the deep South Atlantic and North Pacific: new genus, new species and new records. PeerJ. 8: e9431. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.9431

Contacts:

Cristiana Castello Branco (brancoc@si.edu; cristianacbranco@gmail.com), co-author of the new species

Allen Collins (allen.collins@noaa.gov), co-author of the new species

Eduardo Hajdu (eduardo.hajdu@gmail.com), co-author of the new species

Image available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&tid=1446846&pic=147536

More images available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=1446846#images

Other media:

https://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/news/oer-updates/2020/sponge-discovery.html

The Patrick Sea Star

Original source:

Zhang, R.; Zhou, Y.; Xiao, N.; Wang, C. (2020). A new sponge-associated starfish, Astrolirus patricki sp. nov. (Asteroidea: Brisingida: Brisingidae), from the northwestern Pacific seamounts. PeerJ. 8: e9071. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.9071

Contact:

Ruiyan Zhang (zhangruiyan@sio.org.cn), co-author of the new species

Chunsheng Wang (wangsio@sio.org.cn), co-author of the new species

Image available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&tid=1439894&pic=147453

More images available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=1439894#images

The Branch-Armed Nostril Copepod

Original source:

Irigoitia, M.M.; Taglioretti, V.; Timi, J.T. (2020). Dendrapta nasicola n. sp. (Copepoda: Siphonostomatoida: Lernaeopodidae) a parasite from the olfactory sacs of Bathyraja scaphiops (Norman, 1937) in the South Western Atlantic. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 92(2). https://doi.org/10.1590/0001-3765202020180933

Contact:

- Manuel Marcial Irigoitia (mmirigoitia@mdp.edu.ar), co-author of the new species

Image available at:

More images available at:

The Yellow Sea Slug of Ørland

Original source:

Korshunova, T.; Bakken, T.; Grøtan, V. V.; Johnson, K. B.; Lundin, K.; Martynov, A. (2020). A synoptic review of the family Dendronotidae (Mollusca: Nudibranchia): a multilevel organismal diversity approach. Contributions to Zoology. 90(1): 93-153. https://doi.org/10.1163/18759866-BJA10014

Contacts:

Torkild Bakken (torkild.bakken@ntnu.no), co-author of the new species

Image available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&tid=1457495&pic=147547

More images available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=1457495#images

Other media:

https://norwegianscitechnews.com/2020/09/divers-discover-new-species-in-orlandet-municipality/

The Giant Plastic Amphipod

Original source:

Weston, J.; Carrillo-barragan, P.; Linley, T.D.; Reid, W.D.K.; Jamieson, A. J. (2020). New species of Eurythenes from hadal depths of the Mariana Trench, Pacific Ocean (Crustacea: Amphipoda). Zootaxa 4748(1): 163-181. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4748.1.9

Contact:

Johanna Weston (j.weston2@ncl.ac.uk), co-author of the new species

Alan Jamieson (alan.jamieson@ncl.ac.uk), co-author of the new species

Image available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&tid=1424175&pic=147551

More images available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=1424175#images

Associated links:

Video of the computer-generated reconstruction of Eurythenes plasticus and its discovery: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=phAFW05eKI8&ab_channel=WWFInternational

Video of Dr Alan Jamieson and Johanna Weston describing Eurythenes plasticus: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QBqQi6xLdww&ab_channel=WWF-Belgium

Dedicated educational website: https://www.plasticus.school/en/

Haffi’s Upside-Down Tapeworm

Original source:

Bray, R.A.; Waeschenbach, A.; Littlewood, D.T.J.; Halvorsen, O.; Olson, P.D. (2020). Molecular circumscription of new species of Gyrocotyle Diesing, 1850 (Cestoda) from deep-sea chimaeriform holocephalans in the North Atlantic. Systematic Parasitology. 97(3): 285-296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11230-020-09912-w

Contact:

Rod Bray (r.bray@nhm.ac.uk), co-author of the new species

Images available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&tid=1433682&pic=147442

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&tid=1433684&pic=147452

More images available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=1433682#images

The Beautiful Branching Bryozoan

Original source:

Harmelin, J.-G. (2020). The Mediterranean species of Hornera Lamouroux, 1821 (Bryozoa, Cyclostomata): reassessment of H. frondiculata (Lamarck, 1816) and description of H. mediterranea n. sp. Zoosystema 42(27): 525-545. https://doi.org/10.5252/zoosystema2020v42a27. http://zoosystema.com/42/27

Contact:

Jean-Georges Harmelin (jean-georges.harmelin@mio.osupytheas.fr or jg.harmelin@gmail.com), author of the new species

Image available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&tid=1463551&pic=147554

More images available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=1463551#images

Other media:

From “Parc National des Calanques”, a video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cGY6n5I_-Vo

The Tree-of-Life Tardigrade

Original source:

Møbjerg, N.; Jørgensen, A.; Kristensen, R.M. (2020). Ongoing revision of Echiniscoididae (Heterotardigrada: Echiniscoidea), with the description of a new interstitial species and genus with unique anal structures. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 188 (3): 663–680 https://doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zlz122

Contact:

Nadja Møbjerg (nmobjerg@bio.ku.dk), co-author of the new species

Image available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&tid=1479074&pic=147559

More images available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=1479074#images

The Feisty Elvis Worm

Original source:

Hatch, A. S.; Liew, H.; Hourdez, S.; Rouse, G. W. (2020). Hungry scale worms: Phylogenetics of Peinaleopolynoe (Polynoidae, Annelida), with four new species. ZooKeys 932: 27-74. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.932.48532

Contacts:

Avery S. Hatch (ahatch@ucsd.edu), co-author of the new species

Greg W. Rouse (grouse@ucsd.edu), co-author of the new species

Image available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&tid=1436333&pic=147565

More images available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=1436333#images

Other media:

https://www.insidescience.org/news/new-worm-species-jewel-scales-discovered-deep-ocean-darkness

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lgQvuYljX8g

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CbWKfKfAve8

Red Wide-Bodied Pipefish

Original source:

Short, G.; Trevor-Jones, A. (2020). Stigmatopora harastii, a new species of pipefish in facultative associations with finger sponges and red algae from New South Wales, Australia (Teleostei, Syngnathidae). ZooKeys. 994: 105-123. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.994.57160

Contact:

Amanda Hay (Amanda.hay@austmus.gov.au), collection manager

Graham Short (gshort@calacademy.org), co-author of the new species

Andrew Trevor-Jones (andrew.trevor-jones@austmus.gov.au), co-author of the new species

Images available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&tid=1468843&pic=147455

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&tid=1468843&pic=147454

More images available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=1468843#images

Other media: