The acoustic character of an underwater habitat

Just as the doctor listens to the condition of your lungs with his stethoscope, imagine that you can tell how healthy or unhealthy the sea is from the underwater sound. That is what LifeWatch VLIZ engineer Clea Parcerisas wants to find out with her doctoral research on underwater soundscapes.

Many people think that the underwater world is a silent world. But nothing could be further from the truth. There is a cacophony of sounds underwater. The soundscape is the sum of all sounds in a particular place, at a particular time and over a particular period. An underwater soundscape is made up of sounds caused by geological phenomena, such as rain, waves or ice cracking (so-called geophony), but it can also contain sounds of animals (biophony) or human activities (anthropophony). Computer scientist Clea Parcerisas, a PhD student at the Marine Observation Centre of the Flanders Marine Institute (VLIZ) and affiliated with the Information Technology Department (WAVES) of Ghent University, hopes to be able to extract ecological information from the underwater soundscapes at the end of her PhD. She introduces her work in an explainer video.

Clea does not aim to identify sounds of individual species of events in the underwater soundscapes of the Belgian North Sea. Instead she tries to detect the status at habitat level. In this way she tries for example to find out how the sound of life in and on a sandbank differs from that in a muddy gully. To do this, she measures the sound in those different habitats, and that at several moments over a long period of time. Clea: “My hypothesis – that I still have to prove yet – is that the soundscape in a certain habitat can differ greatly depending on temperature, tides, wave height, current strength and other environmental factors. Imagine that all this succeeds, then we will eventually be able to score the health of a certain ecosystem, based solely on the noise we measure there.”

Collecting long-term data thanks to LifeWatch programme

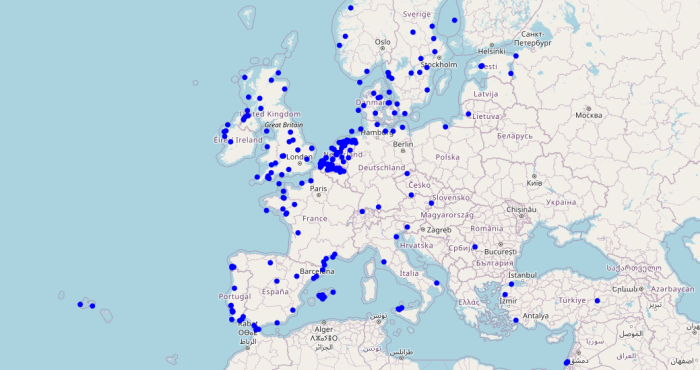

The more data that is collected in different places and over a longer period of time, the better it is to monitor annual and seasonal patterns. And that takes time. "But to draw valuable ecological conclusions you need to be able to look beyond the snapshot of the moment or daily variations," says Elisabeth Debusschere, Clea's supervisor at VLIZ's Marine Observation Centre. " Such a long-term monitoring is made possible by the Lifewatch Belgium programme." A lot of data over a long time also means many hours at sea, and that is not always evident in the turbulent North Sea.

"Together with other colleagues from Lifewatch Belgium, we worked on a solution to make the measurements at sea automatic. We placed the hydrophone on a stainless steel frame (or so-called mooring), which we can leave on the bottom of the sea for a longer period of time. Other LifeWatch colleagues also use the same moorings to hang equipment to detect, for example, the movement of fish or the sounds of marine mammals. After several months, we retrieve the frames and read the data. This used to be done by divers. Now we use a special system so that the mooring can be retrieved remotely from the ship. After sending an acoustic signal, an acoustic release system is activated. Buoys with a high buoyancy are released and bring a rope to the water surface, after which the entire construction can be hoisted from the ship using the crane.

Read the whole Dutch article on the VLIZ Testerep Magazine.

Clea does not aim to identify sounds of individual species of events in the underwater soundscapes of the Belgian North Sea. Instead she tries to detect the status at habitat level. In this way she tries for example to find out how the sound of life in and on a sandbank differs from that in a muddy gully. To do this, she measures the sound in those different habitats, and that at several moments over a long period of time. Clea: “My hypothesis – that I still have to prove yet – is that the soundscape in a certain habitat can differ greatly depending on temperature, tides, wave height, current strength and other environmental factors. Imagine that all this succeeds, then we will eventually be able to score the health of a certain ecosystem, based solely on the noise we measure there.”

Collecting long-term data thanks to LifeWatch programme

The more data that is collected in different places and over a longer period of time, the better it is to monitor annual and seasonal patterns. And that takes time. "But to draw valuable ecological conclusions you need to be able to look beyond the snapshot of the moment or daily variations," says Elisabeth Debusschere, Clea's supervisor at VLIZ's Marine Observation Centre. " Such a long-term monitoring is made possible by the Lifewatch Belgium programme." A lot of data over a long time also means many hours at sea, and that is not always evident in the turbulent North Sea.

"Together with other colleagues from Lifewatch Belgium, we worked on a solution to make the measurements at sea automatic. We placed the hydrophone on a stainless steel frame (or so-called mooring), which we can leave on the bottom of the sea for a longer period of time. Other LifeWatch colleagues also use the same moorings to hang equipment to detect, for example, the movement of fish or the sounds of marine mammals. After several months, we retrieve the frames and read the data. This used to be done by divers. Now we use a special system so that the mooring can be retrieved remotely from the ship. After sending an acoustic signal, an acoustic release system is activated. Buoys with a high buoyancy are released and bring a rope to the water surface, after which the entire construction can be hoisted from the ship using the crane.

Read the whole Dutch article on the VLIZ Testerep Magazine.