Publication date: January 19th 2023

The original title we had in mind for this week's story was “Taxonomic problem solving: dark literature”. But when starting our research and writing in order to explain what we mean by this, we had a hard time matching what we meant with the actual definition of ‘dark literature’.

When consulting Google on the term ‘dark literature’, you almost automatically end up with ‘Gothic literature’, which is often referred to as “tales of horror”. This dark or Gothic literature is described as "a genre of literature that combines dark elements, spooky settings, conflicted and disturbed characters into a whimsically horrific, often romantic, story”. Well, we know from one of our previous stories that science can be described as an art, a science or a battleground (Story 7), but we never encountered anyone who has referred to it as ‘horror’ except maybe for some students who take their first steps in species identifications and are confronted with challenging or cryptic species!

So, what do we mean by ‘dark literature’?

The digital era has made access to literature a lot easier. Initiatives such as the Biodiversity Heritage Library (BHL) are a time-saving gift, and provide access to old literature all over the globe. Within WoRMS, a simple link to BHL can be added, so the actual pdf does not need to be stored at WoRMS itself. The internet and emails allow a very quick exchange of rare literature which might be stored in personal libraries.

Available digital literature - the challenge of published versus unpublished

A specific publication, really an unpublished but cited manuscript, that has given our Steering Committee a headache is that of Renier, 1804. This publication contains more than 50 new species names, but was defined as an unavailable publication according to ICZN Opinion 316. This opinion was entitled: “rejection for nomenclature purposes of the “Tavola Alfabetica delle Conchiglei Adriatiche” and “Prospetto Bella Classe dei Vermi'' of S.A. Renier commonly attributed to the year 1804”. Part of the reasoning of the Commission relates to the author name not being printed on pages and the date, while commonly given as 1804, is actually uncertain. So, the ruling of the ICZN Commission seems clear, no? Not really, as some names from this work were validated later by ICZN Opinions. So not all the names in Renier, 1804 can be ignored… and some of the names from this work have been cited in other works even though they are unavailable, so they should ideally be documented within WoRMS with reference to this particular ICZN Opinion, or the subsequent ones overruling this original opinion for some of the names. Only this way, WoRMS will be able to provide a full overview of all names ever published, with a clear statement on their current and historical status.

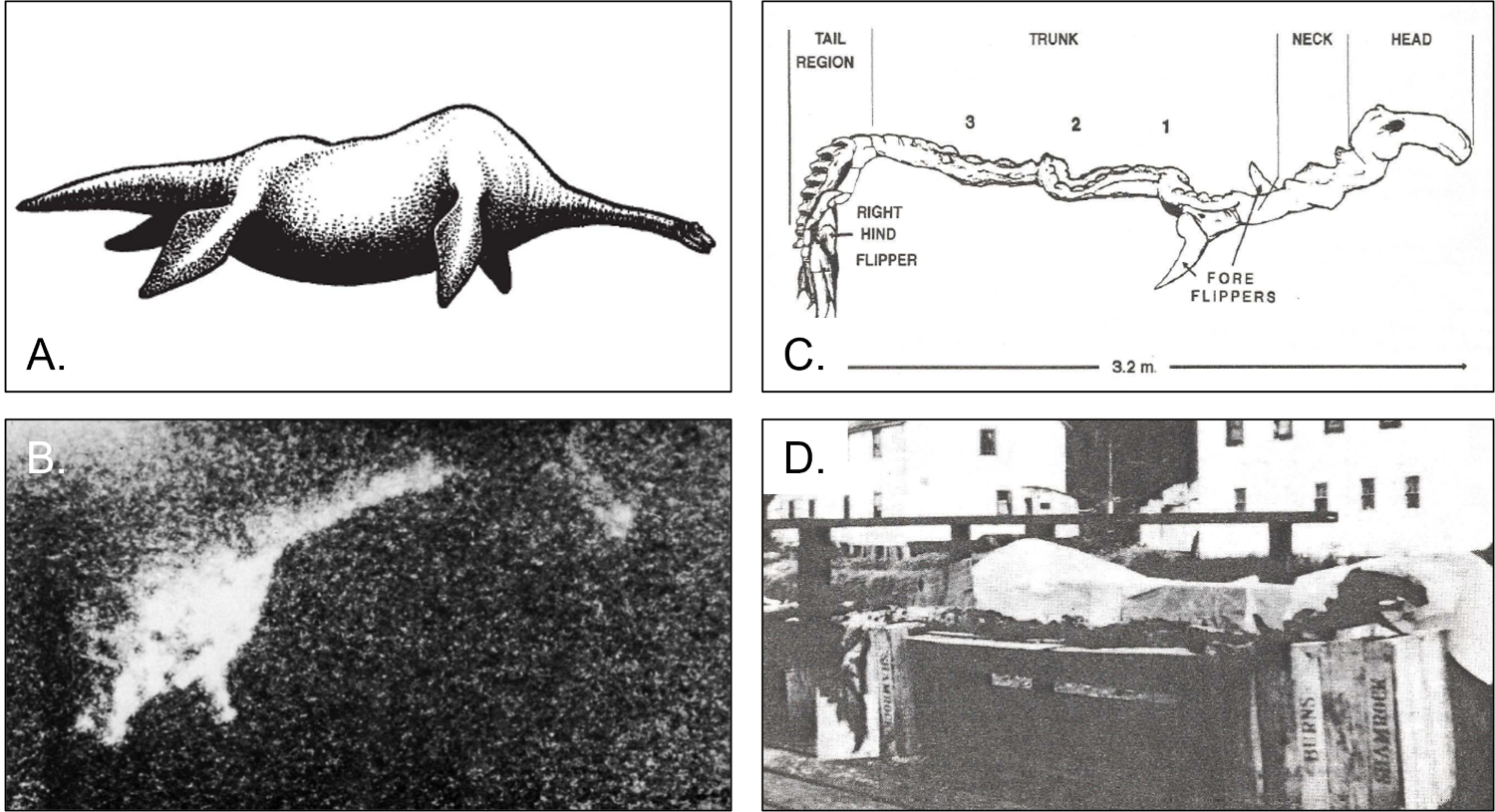

A. Impression of the possible appearance of Nessiteras rhombopteryx from photographs, eyewitness accounts and sketches derived from a large number of sightings at the surface and from the accompanying underwater pictures. (Scott & Rines, 1975) ----- B. Photograph taken by strobe flash at a depth of 35 feet in 80 feet or more of water in Loch Ness at 0430 h on June 20, 1975, showing the head and neck (7-12 feet in length) together with part of the body, with appendages, of Nessiteras rhombopteryx. The main body structure is 20-25 feet from the camera which is pointing about 30° above horizontal. Adjacent frames, taken about 1 min before and 1 min after, show nothing. (Copyright, Academy of Applied Science, Boston, Massachusetts.) (Scott & Rines, 1975) ----- C. Trace Outline of Juvenile Cadborosaurus, Naden Harbour, B. C. (from G. V. Boorman photograph (Holotype), antero-lateral view). (Bousfield & LeBlond, 1995) ----- D. Juvenile Cadborosaurus, Naden Harbom: B. C., July, 1937 Antero-lateral View. G. V. Boonnan photo (Holotype). (Bousfield & LeBlond, 1995)

Science or fiction - a thin line in taxonomy?

And what about “fictional science” in literature? In one of our previous stories, we already made reference to the creativity of scientists in naming species (Story 7) and getting their inspiration from science fiction movies. But what happens when scientists decide to name non-existing species following the requirements of the International Nomenclatural Code, and these descriptions get published?

Until very recently, the Data Management Team was largely unaware that this had happened. An example we learned about, is the official and valid description of the completely fictional creature, the Marsupilami. Although it absolutely does not exist - except in the comic strips by André Franquin - it was validly described according to the Code regulations. So it could be debated whether this species should become part of global species registers. Venturing further into this, a user pointed us to the field of Cryptozoology, described as a field that searches for and studies unknown, legendary or extinct animals, whose present existence is disputed or unsubstantiated, particularly looking at species popular in folklore. A well-known example is the Loch Ness monster, as are the Yeti and Bigfoot. Now, we can hear you think: ““these are not marine, so no need to consider or debate whether these need to be added to WoRMS.” Well… we also learned about at least one marine example: the Cadborosaurus, a large aquatic but dubious reptile from the Pacific coast of North America, which was even recommended to be considered for the COSEWIC list of rare and endangered species of Canada! Similar to the Loch Ness monster, the Cadborosaurus description was largely based on ethnological, testimonial and photographic evidence, and several debates question the validity of all the presented evidence, as is the case with other crypto-species.

Since WoRMS is still catching up with all published taxon names or regularly observed species since the time of Linnaeus, we still have a long way to go before WoRMS will be able to start exploring the need and possibilities to include these dubious species in the Register… or not…!

References:

- [Renier, S. A.]. ([1804]). Prospetto della Classe dei Vermi Nominati e Ordinati secondo il Sistema di Bosc [Work No. 25 on the Official Index of Rejected and Invalid Works in Zoological Nomenclature; see ICZN Opinion 316.]. [Page proofs of introductory book text in folio sheets, never published]. xv-xxvi [Padua, Italy].

- Quintart, A. (1989). Le Marsupilami, une espèce nouvelle pour la science. Nat. Belges 70(4): 153-157

- Scott, P.; Rines, R. (1975). Naming the Loch Ness monster. Nature (Lond.) 258(5535): 466-468. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/258466a0

- Bousfield, E.L.; LeBlond, P.H. (1995). An account of Cadborosaurus willsi, new genus, new species, a large aquatic reptile from the Pacific coast of North America. Amphipacifica 1(Suppl. 1): 1-25

- Eberhart, G.M. (2002). Mysterious creatures: A guide to cryptozoology. ABC-CLIO, Inc.: Santa Barbara. ISBN 1-57607-283-5. xlvii, 723 pp.

- http://allwritefictionadvice.blogspot.com/2017/09/what-makes-story-dark.html

- https://tetzoo.com/blog/2020/11/16/cadborosaurus-carcass-review

Image credit

Contact

WoRMS Data Management Team - info@marinespecies.org

Acknowledgements:

This celebration and series of news messages initiated by the Data Management Team (DMT) would not have been possible without the collaboration of the WoRMS Steering Committee (SC) & voluntary contributions by many of the WoRMS editors.

The work of the DMT and many WoRMS-DMT-related activities are supported by LifeWatch Belgium, part of the E-Science European LifeWatch Infrastructure for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Research. LifeWatch is a distributed virtual laboratory, which is used for different aspects of biodiversity research. The Species Information Backbone of LifeWatch aims at bringing together taxonomic and species-related data and at filling the gaps in our knowledge. In addition, it gives support to taxonomic experts by providing them logistic and financial support for the organization of meetings and workshops related to expanding the content and enhancing the quality of taxonomic databases.

WoRMS – as ABC WoRMS – is an endorsed action under the UN Ocean Decade.

Note: as is the case for previous stories and their highlighted examples, many more examples are available within WoRMS. The highlighted examples are either well-known to the Data Management Team through close interactions with the related editor-groups or through discussions within the Steering Committee. It is by no means the intention of the DMT to favour any group or species over another. The names of all species are equally important to be documented within WoRMS.